- bruteforce.so - used to brute force login credentials of WordPress and Joomla sites

- bruteforceng.so - same as above, but with HTTPS and regex support and higher configurability

- cmsurls.so - used to identify WordPress login pages

- crawler.so - used to crawl websites to find WordPress and Joomla sites

- crawlerng.so - an improved version of the above, with HTTPS and regex support, capable of finding webpages matching any regular expression

- crawlerip.so - same as above, but receives a list of target IPs instead of domains

- ftpbrute.so - used to brute force login credentials of FTP servers

- rfiscan.so - used to look for websites with RFI vulnerabilities

- wpenum.so - used to enumerate users of WordPress sites

- opendns.so - used to search for open recursive DNS resolvers

- heartbleed.so - used to identify servers exhibiting the so called Heartbleed-vulnerability (CVE-2014-0160)

This post will not go into great detail about each module individually, but will cover some of our more interesting findings.

bruteforce.soThe bruteforce.so -module is the by far the most common module in active use right now (more on this later). It is quite simple in functionality. It takes a target url pointing to the login page of a WordPress or Joomla site, a file listing usernames and a file listing passwords. Then it tries to log in with every possible username and password combination.

bruteforceng.soThis module is an advanced version of the bruteforce.so -module with added support for HTTPS and regular expressions. In addition to taking as input a target url, a file of usernames and a file of passwords, this module also requires a rule file. The rule file is used to specify the login interface of the targets. Therefore this module can be used to brute force the login credentials of any web-based interface. We have observed this module being used mainly to brute force the login credentials of WordPress and Joomla sites. However, we have reason to believe it has also been used against other kinds of sites, for example cPanel Web Host Manager sites.

What is interesting to note is that we recently uncovered new versions of the bruteforce.so and bruteforceng.so modules. Whereas the old versions tried all the usernames in the username -file against all targets, the new versions allow the C&C to specify a single username to use. The command string used by the C&C to specify target urls is "Q,target" where 'target' is the url. Commands to the new versions however support a longer command string, "Q,target;username". Note the addition of a semi-colon and another parameter. This additional parameter can specify a single username that is then combined with all passwords in the password file. If, however, the username string is 'no_matches' or no second parameter is specified, the module falls back to the old method of trying every username in a separate username file.

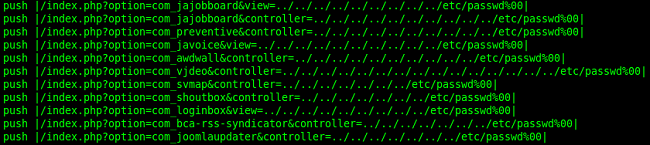

crawlerng.so The crawlerng.so -module is used to crawl websites. It takes as argument a file containing regular expressions. It then searches target domains for content matching those regular expressions. It seems to be mainly used for identifying login pages of WordPress and Joomla sites. However, due to its rules being regular expressions, the module can be instructed to identify essentially any kinds of pages. As an example, we have also observed the crawlerng.so -module being used to identify PhpMyAdmin, DirectAdmin and Drupal login pages. In some cases, the module has been used to find websites featuring content matching specific keywords, for instance pharmacy -related keywords. In one case we even observed the malware operator(s) getting creative and using the crawlerng.so -module to look for local file inclusion -vulnerabilities. Most of the rulesets we have observed have also instructed the module to search for links leading to other HTTP-, HTTPS- or FTP-sites. In this way the module keeps finding new targets to crawl.

Some of the rules used to look for LFI vulnerabilities.opendns.so

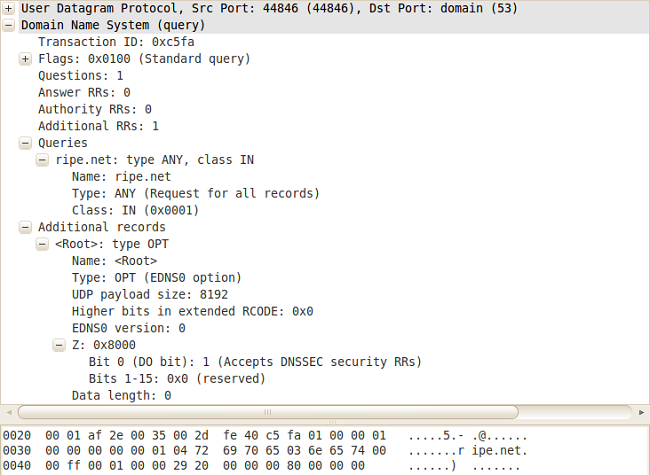

Some of the rules used to look for LFI vulnerabilities.opendns.soThis module is used to search for open recursive DNS resolvers that could be used in DNS amplification attacks. The module takes as argument an IP address range and a threshold size. It then iterates through all IPs in the range attempting to connect to port 53 at each one. If it successfully connects to port 53, it next sends a DNS request asking for ANY records for the domain 'ripe.net' with recursive and extended DNS 'DNSSEC OK' -bits set. If the target is running an open recursive DNS resolver, it will reply with a large DNS answer. The size of the reply is compared to the previously set threshold size and if it is larger, the IP address is reported back to the C&C.

Packet capture of the DNS request sent by the module.heartbleed.so

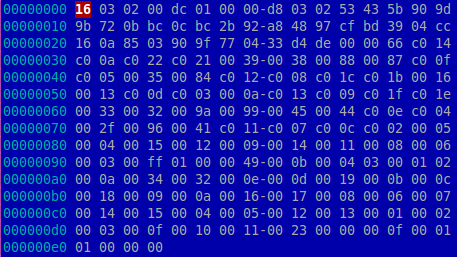

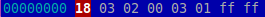

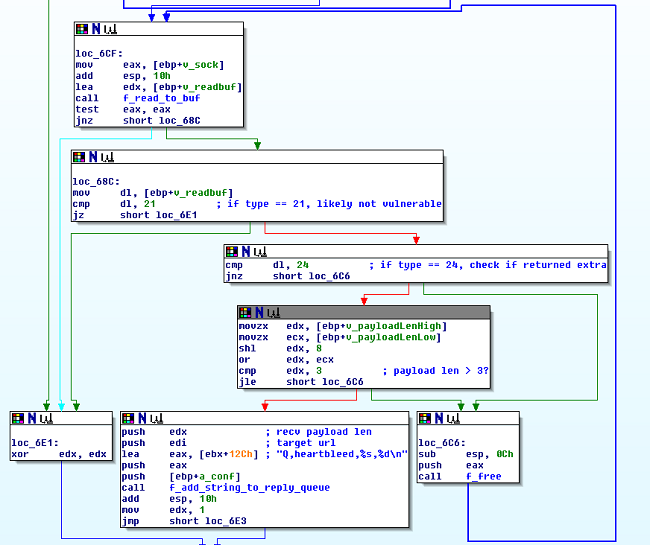

Packet capture of the DNS request sent by the module.heartbleed.so This module tries to identify whether a target domain is vulnerable to the Heartbleed-vulnerability. It does this by first connecting to the target, then sending it a TLSv1.1 ClientHello packet followed by a heartbeat request with a payload size of 64KB (0xFFFF bytes) but an actual payload of only 3 bytes.

The payloads of the ClientHello packet (above) and the malicious heartbeat request.

The payloads of the ClientHello packet (above) and the malicious heartbeat request.Finally, the size of the payload in the server reply is checked. If it is larger than 3 bytes, the server is probably vulnerable and this is reported to the C&C.

Code that checks the server reply.Current activity

Code that checks the server reply.Current activityOur research has uncovered 19 C&C domains used by the Mayhem malware family. Of these, 7 are currently active. Most of the current activity is related to the brute forcing of WordPress and Joomla login credentials. However we have also observed the brute forcing of FTP login credentials as well as the crawling of domains in search of WordPress and Joomla login pages. We also have evidence of other modules being used in the wild at one time or another.

From our observations of the brute forcing activity, it seems highly opportunistic. The malware operator(s) seem to focus on volume and rely on enough sites using common and weak credentials. During a week of logging target urls from the active C&C servers, we identified over 350 000 unique targets. Of these, a single C&C server was responsible for over 210 000 unique targets. It should be noted, that these are only the targets given to single instances of the malware, so the total volume is probably much larger.

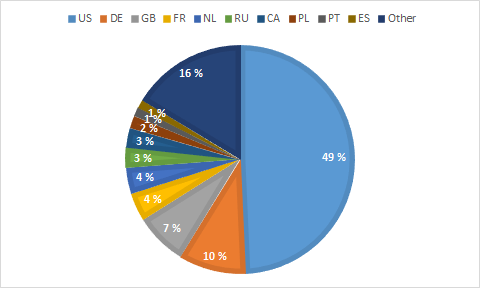

Based on our analysis of target domains, we don't believe the malware operator(s) to be targeting anyone or anything specifically. Rather, we believe they are simply searching for the web's low hanging fruit. This is further supported by the geographic distribution of target domains as seen below. The absence of China from the top 10 is notable, but we believe this to be an anomaly rather than an intentional choice on the part of the malware operator(s).

Conclusions

ConclusionsWe believe the malware operator(s) use Mayhem primarily as a reconnaisance tool and to gain access to easily compromised servers that can later be used as a base for more sophisticated attacks. As an example, the operator(s) might first use the crawlerng.so -module to find WordPress sites, then enumerate potential victim usernames from those sites using the wpenum.so -module. Armed with a list of usernames, the operator(s) can turn to the bruteforce.so -module to attempt to gain access to those sites. Once they have gained access, they can either infect it with Mayhem to expand their botnet, or possibly use it for mounting other operations.

The Mayhem family of malware is an advanced and extremely versatile threat operating on Linux and FreeBSD servers. It is clearly under active development and its operator(s) actively try to counter the efforts of researchers and server administrators. The size of the operation is also significant taking into account the fact that all of the infected hosts are servers with high capacity and bandwith, not your run-of-the-mill home PCs behind a slow ADSL.

Sample hashesVersion 1

- 0f1c66c3bc54c45b1d492565970d51a3c83a582d

- 5ddebe39bdd26cf2aee202bd91d826979595784a

- 6c17115f8a68eb89650a4defd101663cacb997a1

Version 2

- 7204fff9953d95e600eaa2c15e39cda460953496

- 772eb8512d054355d675917aed30ceb41f45fba9

Version 3 (newest)

- 1bc66930597a169a240deed9c07fe01d1faec0ff

- 4f48391fc98a493906c41da40fe708f39969d7b7

- 6405e0093e5942eed98ec6bbcee917af2b9dbc45

- 6992ed4a10da4f4b0eae066d07e45492f355f242

- 71c603c3dbf2b283ab2ee2ae1f95dcaf335b3fce

- 7b89f0615970d2a43b11fd7158ee36a5df93abc8

- 90ffb5d131f6db224f41508db04dc0de7affda88

- 9c7472b3774e0ec60d7b5a417e753882ab566f8d

- a17cb6bbe3c8474c10fdbe8ddfb29efe9c5942c8

- ab8f3e01451f31796f378b9581e629d0916ac5a5

- c0b32efc8f7e1af66086b2adfff07e8cc5dd1a62

- c5d3ea21967bbe6892ceb7f1c3f57d59576e8ee6

- cb7a758fe2680a6082d14c8f9d93ab8c9d6d30b0

- e7ff524f5ae35a16dcbbc8fcf078949fcf8d45b0

- f73981df40e732a682b2d2ccdcb92b07185a9f47

- fa2763b3bd5592976f259baf0ddb98c722c07656

- fd8d1519078d263cce056f16b4929d62e0da992a

We detect these as

Backdoor:Linux/GalacticMayhem.AWritten and researched by Artturi Lehtio (

@lehtior2).

Author's noteI'm a computer science student at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland. After attending a

course this spring on malware analysis, offered by Aalto University and run by F-Secure, I was lucky enough to get hired by F-Secure for a summer internship. A month ago I was given a new task: "go find an interesting looking piece of Linux malware with the goal of writing a blog post about it". The above post and the research to back it up, are the results of my adventure into the mysterious world of Linux malware.